The MV Ever Given was freed on Monday afternoon, six days after becoming stuck in the Suez Canal. Traffic is moving again, but the downstream effects will play out over the coming weeks and the implications are likely to reverberate through the international shipping industry for years.

The incident: How the vessel – at 20,124 TEU capacity, one of the world’s largest – wound up wedged into the canal wall will be the subject of an investigation. As in the Panama and St Lawrence waterway, vessels transiting the Suez are placed under the command of specialized pilots, and human error could always be a factor. Reports from the time of the grounding noted a sandstorm with winds up to 40 knots and reduced visibility, but these alone should not be sufficient to push an ocean going vessel off course, and the Ever Given was one of approximately 15 ships traveling north through the canal in convoy when the incident occurred. The sheer size of the ship may also be relevant: opened in 1869, the Suez was expanded in 2015 but cannot keep pace with the shipping industries appetite for ever-larger vessels.

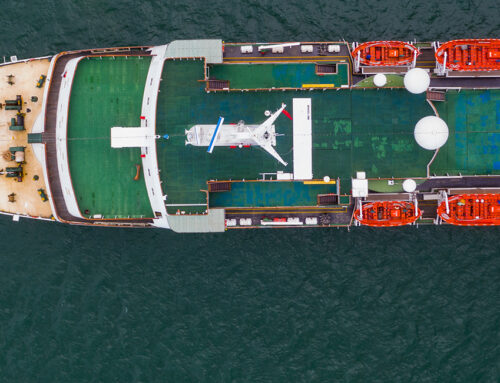

The tide turns: The vessel was freed by a combination of dredging operations at the bow, carried out by two massive dredgers operated by the Suez authority, and as many as 14 tugboats. The effort was led by Dutch salvage experts Boskalis. But the final push came from mother nature: surprisingly, the Suez canal has no locks, and seawater flows freely up and down the waterway in accordance with the tides and with seasonal conditions. A natural high tide coinciding with yesterday’s full moon helped push salvage efforts over the top, making the unloading of the vessel – a long and expensive process – unnecessary. The canal itself is undamaged, and cargo started moving again almost immediately, with three livestock carrying vessels given priority.

Traffic Congestion: Traffic through the canal has been entirely stopped for almost exactly a week; normally, about fifty vessels transit the canal per day, meaning there are hundreds of vessels backed up on both sides of the Suez. The narrow artery carries approximately 12% of global trade, estimated at $9 billion per day, meaning there is more than $50 billion in cargo queued up on 437 waiting vessels. The impact will be felt most acutely in European ports, where capacity will be taxed by the backlog, exacerbating equipment availability and related problems already resulting from Covid-19. Already high, freight rates will remain high or even increase further over the short term.

Not much hope: Traffic data show that a significant number of vessels re-routed around the Cape of Good Hope to avoid what might have been a much more prolonged incident. As it adds eight to ten days to the voyage, those re-routing decisions will probably result in relatively little change in terms of overall voyage duration. The CEO of Maersk, which re-routed at least 15 vessels, noted that the incident highlights the fragility of “just-in-time” delivery systems. Companies will increasingly look to “just in case” supply chains, giving up some small cost savings up front for a more robust system with multiple suppliers and less risk.

Global Infrastructure: The incident highlights the fragility of global supply chains and key infrastructure like the Suez and Panama canals. It also highlights the dependence of all nations, but particularly of China, on smooth international trade: China requires a robust global shipping industry both to supply its need for raw materials such as coal and steel, as well as to sustain the export of manufactures that pay for those supplies. Writing in Time Magazine, Admiral Stavridis (Ret.) argues that these choke points – as well as the straits of Malacca and Hormuz – must be viewed from a perspective of global maritime security, placed under international authorities with – importantly – international funding for preventing and responding to crises.